Signs of Confusion & Questions! Second Review On "The Princes In The Tower: A Damned Discovery"!

- Sez Francis

- Dec 11, 2024

- 22 min read

Originally Published 11th December 2024

This is the initial section of the theory regarding the skeletons of the Princes in The Tower. For the previous section, click here.

The phrase "smoking gun" continues to attract significant attention on Google, with search results about the Princes in the Tower potentially arising from sensationalist journalism or indicative of a moment of authentic intrigue. However, I shall refrain from elaborating on this matter, as I have examined it in greater detail in my previous article.

Instead, I will proceed with my evaluation of the British Channel 5 documentary, "The Princes in the Tower: A Damning Discovery."

Before proceeding again, I want to clarify that although I deeply respect differing opinions, this critique is based on my perspective and research. In addition to watching the documentary, I have consulted various sources and viewpoints from historians and enthusiasts, including Matthew Lewis, Dan Jones, John Ashdown-Hill, and R.L. Weston of History Calling. Furthermore, I have examined research by Professor Tim Thornton of the University of Huddersfield, who was featured in the documentary, and I plan to revisit the report from the 1933 examination. If you want to access Professor Thornton's articles, I will provide links in the references section. This review will be presented in three parts, with this section as the first. Now, let us proceed with the analysis.

Case 3b: Richard of Shrewsbury's Whereabouts

In the preceding post, I examined Edward V.'s movements and life. This discussion will now shift focus to Richard of Shrewsbury, the Duke of York. After viewing the documentary, I noticed that neither Tracy Borman nor Jason Watkins adequately explained Richard of Shrewsbury’s location while his elder brother was in Ludlow, London, and the Tower between April and June 1483.

Borman noted that as Edward V and the royal entourage entered London from Stoney Stratford, Richard stayed there with his sisters, mother, step-brother, the Marquess of Dorset, and his second maternal uncle, the Bishop of Salisbury, until mid-June. However, I find Borman's assertion problematic, particularly her reference to armed supporters of the Duke of Gloucester surrounding Westminster Abbey. This depiction is misleading, as no definitive records support the presence at Westminster Abbey. The family sought sanctuary at Cheneygates Mansion on May 1st, around the same time Edward V, Buckingham, Gloucester, and the royal entourage were in Hertfordshire before entering London. Tragically, Richard of Shrewsbury would remain at the mansion for less than two months.

While there is no evidence to suggest that the family was held captive by supporters of the Duke of Gloucester, there are indications that Gloucester pressured Queen Dowager to turn Richard over to him. The term, "applied pressure", can be interpreted in two ways: either Gloucester had nefarious intentions or was genuinely concerned for the safety of his younger nephew.

Historian Dan Jones articulates the first narrative. In his publication, The Hollow Crown, Jones addresses the gaps in the timeline between Edward V's arrival at the Tower of London on May 19th and the eventual surrender of Richard of Shrewsbury into the Duke of Gloucester's custody by the Queen Dowager. After Gloucester was officially appointed as protector on May 9th, he moved to Crosby Place on Bishopsgate, rumoured to be a staging ground for a coup against the Woodvilles while conducting government affairs. In early June, Gloucester sent letters to loyal servants in Yorkshire, soliciting military support to converge on London. He convened a council meeting in Westminster, attended by Queen Elizabeth Woodville after she emerged from the sanctuary. During this meeting, reportedly held on June 9th, the Queen Dowager remained silent despite the four-hour meeting and the presence of various attendees.

As noted by Wendy E.A. Moorhen, the Queen Dowager also attended a subsequent meeting on June 12th; however, there are no additional records detailing the proceedings of that gathering.

Following Lord Hastings' execution the next evening, the Queen Dowager likely experienced confusion and a heightened sense of urgency, especially, upon learning of Gloucester’s postponement of the coronation, which was rescheduled for November 9th. It seems plausible that she perceived significant disturbances in the political landscape.

When Richard left Cheneygates Mansion on June 16th, he was escorted by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Upon departing the mansion, Richard encountered his uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, and the Duke of Buckingham outside the Star Chamber Door, which is currently within the precincts of Westminster School. According to the account of Canon Simon Stallworth, who was present at the council meeting on June 9th, he documented the actions of the Duke of Gloucester as follows:

'My lord protecter recieving him at the Star Chamber Door with many loving words and so departed with my lord Cardinal to the tower, where he is, blessed be Jesus, merry'.

Following an audience with the Duke of Gloucester, Little Richard was escorted by John Howard, the 1st Duke of Norfolk, to the Tower of London, where he joined Edward V in anticipation of his coronation.

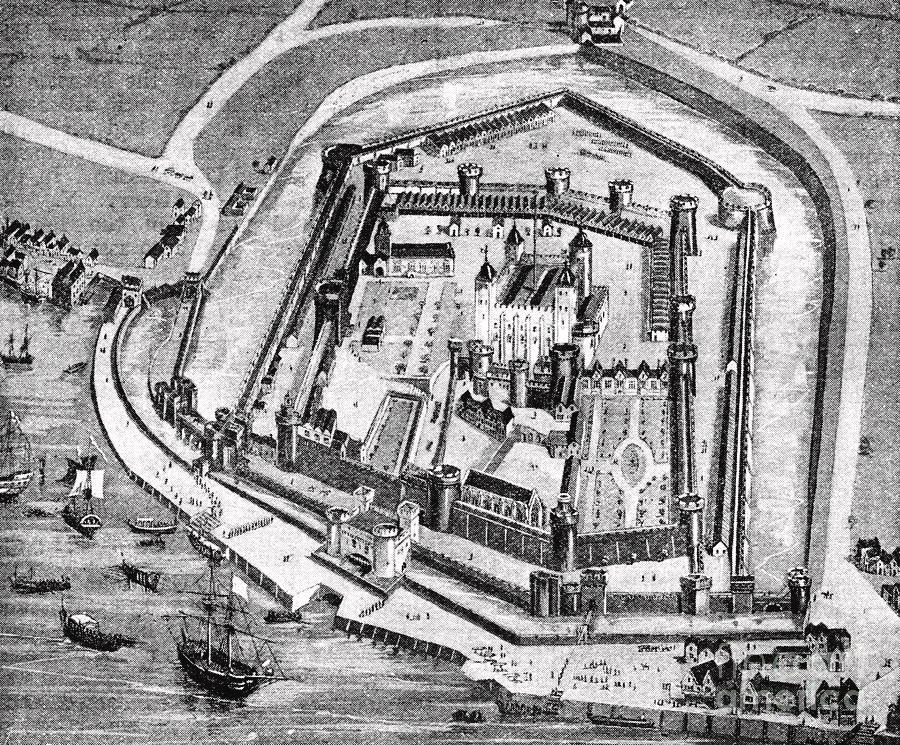

It's important to clarify that the locations of both boys in this stage of the narrative may lead to confusion. While it has been previously stated that Edward V resided in the King's Lodgings within the Tower, Borman asserts that the boys were initially situated in the Garden Tower, currently known as the Bloody Tower. However, this assertion is inaccurate. From June 16 to June 22, Edward and Little Richard were accommodated in the Royal Apartments in the King's Lodging within the Tower.

This argument is further substantiated by a quotation from Ashdown-Hill, who elucidates:

In the Middle Ages, the Tower of London would not chiefly have been seen as a prison. Of course it was a castle, and because they weresecure places, medieval castles were sometimes used to detain people. Indeed, Richard III himself refers in one surviving memorandum to detentions in the 'Toure of London or other prisone'. However, in terms of its main function, in the Middle Ages the Tower of London was roughly the equivalent of the modern Buckingham Palace.

Ashdown-Hill's commentary suggests that the Tower of London functioned as the primary official residence for the Royal family. He indicates that during the reign of Edward IV, the father of the young princes, the King visited the Tower seventy-four times in the year 1482. However, the Tower also served as a place of imprisonment for various royals. For example, John Balliol, the former King of Scots, was confined in the Salt Tower following his capture in 1296. Similarly, in 1356, Jean II of France was housed there; he was detained for ransom before signing the Treaty of Brétigny. Despite his imprisonment, he retained certain royal privileges, permitting him to acquire horses, pets, and clothing and to engage the services of an astrologer and court musicians.

Henry VI of England endured two captures by the Yorkists and was reportedly imprisoned in the Wakefield Tower, where he ultimately died, allegedly murdered within the confines of the King's Private Chapel.

The Duke of Clarence, George Plantagenet, imprisoned for treason against Edward IV, faced execution following a guilty verdict. The exact location of his imprisonment within the Tower of London is uncertain; some accounts suggest that he met his demise by being drowned in a barrel of Malmsey wine.

Ashdown-Hill also references the Crowland Chronicle Continuations (circa 1486), which does not document the young princes inhabiting prison cells but notes that they were under guard. He indicates that a report from December 1483 suggested a transfer of the boys from the King's Lodgings to a more secluded location within the Tower. This implies that they may have been housed in the Lanthorn Tower or in a space east of the King's Lodgings, where they were reportedly observed playing in the Privy Garden.

In conducting further research on the Historic Royal Palaces website, I found that the Lanthorn Tower and the King's Lodgings sections are situated within the Medieval Palace, alongside St. Thomas's Tower and the Wakefield Tower. Additionally, I located a map derived from plans of the Tower of London, published by the Ministry of Public Building and Works, on the Images of Medieval Art and Architecture website. This map illustrates the proximity of the various towers.

A sixteenth-century map from Ashdown-Hill's text depicts sketches of several structures and a substantial hall connecting the Wakefield and Lanthorn Towers, situated near the Wakefield Tower in the southern section of the White Tower. Although these buildings have since been removed, they previously facilitated private access to the King's Lodgings. Consequently, it can be concluded that the Wakefield Tower formed part of the King's Lodgings, implying a considerable establishment.

The Historic Royal Palaces website elucidates that the Lanthorn Tower constituted part of the Queen's Lodgings. This raises questions regarding the rationale for relocating the boys to an accommodation designated for a Queen consort rather than a King or heir to the throne. Further investigation reveals that, following the death of Edward I in 1307, Kings generally took residence in the Lanthorn Tower. Nonetheless, the Wakefield Tower retained its function as a Royal residence, including a private audience chamber for council meetings.

Based on this information, it appears that Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury were initially accommodated in the Wakefield Tower before potentially moving to the Lanthorn Tower, which was historically part of the Queen’s Lodgings. Although this arrangement may seem unusual, it is plausible that the princes transitioned between the two Towers via a lost footbridge or a medieval walkway, now designated as Salvin's Bridge, which linked the Wakefield and St. Thomas' Towers. This connection is corroborated by drawings attributed to Victorian architect Anthony Salvin for the Office of Works; however, it should be noted that these drawings were finalized in 1919, significantly postdating Salvin's death. (Click here to view the sketches)

Borman suggests that the boys were not held as prisoners in a specific location. Instead, they were observed on the premises, interacting with Archey and engaging in various activities. In my opinion, this observation indicates a sense of autonomy, implying that they were not true prisoners. They could participate in activities of their choice, even if they were under supervision.

Case 3c: Succession Crisis and Accession of Richard III

On June 22nd, a sermon was conducted outside Old St. Paul’s Cathedral, where an English theologian presented a discourse. This date was anticipated to be a celebration, as it signified the coronation of Edward V. However, Ralph Shaa (or Shaw), the individual responsible for the sermon, asserted that Edward lacked a legitimate claim to the throne due to his illegitimacy.

In this segment of "A Damned Discovery," Watkins interviews historian Nathan Amin, who elucidates how Shaa's argument cast doubt on Edward V's right to rule. Amin refers to a surviving document that raises questions of illegitimacy concerning the offspring of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, indicating that they may have been born after a pre-contract involving Edward IV and a woman named Eleanor Butler. Amin, however, overlooks the pivotal fact that when Shaa delivered the sermon, Butler had passed away in 1468, four years after Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. Consequently, Butler could not voice her perspective regarding the legitimacy of this marriage.

Despite his focus on Butler, Shaa ultimately concluded in his sermon that the young King and his siblings were "unworthy of Kingship." Watkins subsequently queries whether Richard III orchestrated this surprising revelation. Amin posits that the timing of the sermon was exceedingly convenient and raises doubts regarding Shaa's ability to deliver it without Richard III's endorsement. He states, "This is slanderous to his [Richard III’s] family, and it marks a pivotal point in our story. It signifies the first time the disinheritance of the Princes in the Tower was announced."

While Watkins’ interview with Amin was engaging, it provoked several questions regarding the sermon. One wonders why Shaa did not seek Gloucester’s approval before publicly delivering his speech. It raises suspicions about the underlying motivations. The term "slanderous" prompted a further inquiry into whether Shaa intended to inflict detrimental damage to the Yorkist royal family. Initially sceptical about the notion that Richard might be behind the scenario, I later encountered alternative analyses.

According to Ashdown-Hill, a trusted individual may have compromised Edward IV's marriage to Butler by keeping it concealed. The beginning of this situation can be traced to June 9th, during a council meeting in Westminster, when Bishop Stillington cited the grounds for declaring Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville’s children illegitimate. During his service under Edward IV, Stillington revealed that the deceased King had requested him to marry Butler. Notably, Stillington remained silent regarding this alleged marriage during Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, only speaking out after the Duke of Clarence was informed. It raises the question of whether Stillington disclosed this secret to Clarence, who ultimately faced execution for treason. Stillington was at risk of arrest, but he received a pardon in 1478 and later engaged with the new government. Canon Stallworth, previously mentioned, is believed to have written a letter to Sir William Stonor, a Sheriff from Oxfordshire, in the presence of the Dowager Queen. Following these events, Gloucester sought military support from loyal followers in Yorkshire, intriguingly mirrored by the Duke of Buckingham’s actions in Wales, despite the potential declaration of the boys' illegitimacy at Guildhall on the 25th of June.

The question of whether Edward V was cognizant of this situation remains. Ashdown-Hill speculates that this may be plausible, explaining that while definitive evidence is lacking, it is conceivable that Gloucester regularly visited Edward V at the Tower to discuss governance matters in his capacity as lord protector.

The critical inquiry remains: how did Shaa acquire this knowledge, and from what sources did he derive his information?

One potential explanation involves a half-relative of Shaa. His half-brother, Edmund Shaa, was Lord Mayor of London. Nevertheless, this connection remains inconclusive due to insufficient evidence. Interestingly, in the later stages of his life, Shaa expressed regret regarding delivering the sermon titled "Bastard Slips Should Not Take Deep Root." In an article published in the Richardian Bulletin, author Judith Ford notes that when he drafted his last will on August 18, 1484, Shaa inscribed:

the xviij day of the moneth of Auguste the yere of oure lord god millesimo CCCC lxxxiiij And the second yere of the reigne of king Richard the iijde I Rauf Shaa doctor of Divinyte and one of the residencaries of the cathedrall church of saynt paule ...8 Following a declaration of his mental fitness, the testator observed that ‘beying pore in body oure lord Jhesu be thankyd in every whai withyne this Vale of mysrye [I] make and ordeyn this my present testament conteynyng my last Will in manere and forme ensuyng’.

The excerpt from his will indicates that Shaa, who was once a respected member of the clergy at Old St. Paul's, faced disapproval following a sermon, which led to a decline in his reputation. It remains unclear whether Shaa acted on his own accord or if external factors contributed to his situation.

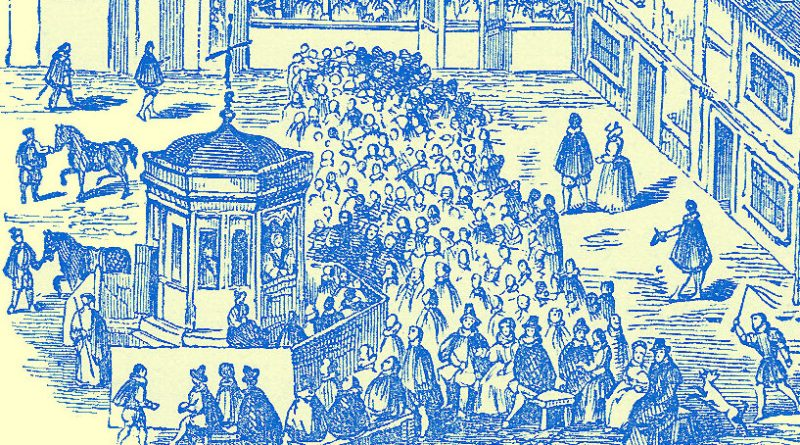

Subsequently, Edward V was deposed, prompting both the citizens of London and members of the nobility, as well as commoners, to petition Gloucester to assume the throne. Gloucester accepted this proposal and became King Richard III. However, the documentary does not address the transition between Edward V's deposition and the Duke of Gloucester's accession as King Richard III, a detail that is not widely known.

In the lineage of kings, Richard III and Edward IV had an elder brother, the Duke of Clarence. Before his execution, Clarence had two children. If Edward V had retained his position as king but produced no heirs, the next in line from the House of York would have been Clarence's younger son, Edward Plantagenet, the Earl of Warwick. Had the Earl ascended the throne and later died without heirs, Richard III would have been next in succession. However, due to Clarence's execution, the Earl of Warwick became ineligible for the monarchy. Additionally, as he was still a minor, the prospect of another child king was not viable. Consequently, with Warwick excluded from the line of succession, Richard III emerged as the only viable candidate for kingship.

Case 3d: Where Did The Princes Go?

Now, we arrive at the final moments concerning the fate of Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury. This section raises numerous questions and concerns, as certain aspects remain unclear. Therefore, I shall explore these details further, which will serve as the conclusion to this analysis. Please prepare for an extensive discussion.

In "A Damned Discovery," limited information is provided regarding the events surrounding Richard III's coronation; however, one significant source, as the title suggests, could have illuminated this topic further. This source is authored by John Ashdown-Hill, who elaborates on these events in "The Mythology of the Princes In The Tower."

Ashdown-Hill indicates that following Richard III's ascension to the throne, unexpected orders were issued, which suggested a concern regarding the boys' disappearance. A notable event occurred between July 1st and 6th, when auxiliary police arrived in London to implement new regulations, including a three-night curfew and a prohibition on citizens carrying weapons. This action followed a letter Richard III dispatched to loyal servants, requesting military support to concentrate in London. Although this research is not referenced in the documentary, it aligns with the belief that there was a protective intent regarding the boys. Historian Tracy Borman asserts that the safety of Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury was paramount to Richard III, noting that "his whole position depends on keeping them safe and here at the Tower where he can see them." This statement is particularly noteworthy, as it implies the possibility that Richard III met with Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury before his coronation while they were purportedly placed "under close watch."

Furthermore, Borman emphasizes that Richard III employed individuals he trusted, including Sir James Tyrell, who will be discussed in a subsequent analysis. Borman concludes that Richard maintained a singular focus. This perspective offers a potential indication of Richard's innocence despite the documentary's implications of his guilt. One must question why Richard would entrust individuals with the care of the boys if they posed a threat to him. If culpability exists in this narrative, it may reside within Tudor propaganda. Notably, the boys were never a substantive threat to Richard III.

The political landscape surrounding Richard III is defined by his perception of individuals as potential threats, particularly regarding the young Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury. Richard may have viewed figures such as Hastings and Elizabeth Shore, the mistress of Edward IV, as supporters of Edward V. Notably, both Hastings and Dorset, along with Elizabeth Woodville's eldest son, were involved with the same mistress, creating a complex and peculiar relationship among these individuals.

It is debatable whether Richard saw his nephews' supporters as direct threats; however, I argue that Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury did not pose a significant danger to their uncle. This assertion remains valid despite Richard's strained relations with the Woodville family. His intense caution seems to stem from a deep-seated paranoia about potential murders. Historian Alison Borman notes that Richard III experienced the loss of both his brother and father during the Battle of Wakefield amid the Wars of the Roses. This tumultuous background likely contributed to a change in his character, making him increasingly ruthless and cold-hearted—an interpretation I find credible. Additionally, it is plausible that Richard III exhibited symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Borman speculates that, despite his paranoia, Richard may have witnessed the murder of King Henry VI within Wakefield Tower, although he might not have been the one to carry it out. The orders for Henry’s murder were reportedly issued by Edward IV, with Richard present as a witness. Nonetheless, the true events that took place in Wakefield Tower in May 1471 remain uncertain.

As we approach Richard's coronation, it is essential to critically examine the preceding events due to the abundance of conflicting sources. A visit to Westminster Hall, featured in a documentary by Amin and Watkins, suggests that Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury were not invited to Richard III's coronation or the accompanying banquet. While there is no definitive evidence to confirm their absence, an intriguing theory comes from the writings of Horace Walpole, who claimed in 1768 that Edward V did attend the coronation after briefly leaving the Tower of London. This assertion is allegedly documented in Richard III’s coronation roll:

To Lord Edward, son of late King Edward the Fourth, for his apparel and array, that is to say, a short gowne, made of two yards and three quarters of crymsy clothe of gold, lyned with two yards 3/4 of blac velvet; a long gowne, made of vi yards D of crymsyn cloth of gold, lynned with six yards of grene damask; a short growne, made of two yards 3/4 of purpell velvett, lyned with two yards 3/4 of green damask; a doublett and a stomacher made of two yards of black satyn &c.

According to my observations, Walpole indicates that Edward V assumed the position of his cousin while walking alongside Richard III. This assertion is predominantly supported by the absence of Edward of Middleham during the coronation of his parents. Although he had not been officially designated as Prince of Wales at that time, Edward of Middleham would have held a significant role in the coronation, particularly in the procession. Walpole posits that Richard III may have requested his nephew to occupy the place of his son, although the motivations for this are not explicitly stated.

Furthermore, Walpole notes that after the directives being issued to don the ceremonial robes for Richard III’s coronation, Edward V articulated specific remarks:

Let no body tell me that these robes, this magnificence, these trappings for a cavalcade, were for the use of a prisoner.

Where was Richard, the Duke of Shrewsbury, during this period? According to Walpole, no arrangements were made for him, as he was not in the custody of his uncle at the time of the coronation.

The veracity of this assertion is subject to debate. Nevertheless, I contend that Richard III may have encountered his nephews within the Tower before the coronation. Although there is no definitive evidence to substantiate this claim, my hypothesis is informed by research regarding the transition from the Lanthorn Tower.

Returning to the relocation from the King's Lodgings, the destination to which the boys were moved remains ambiguous. There appears to be uncertainty surrounding their relocation or even about whether they initially resided in the Garden Tower. The belief that the Garden Tower functioned as either a primary or secondary location is likely a misconception. I have elaborated on this location previously and therefore will not revisit it in detail.

However, upon hearing Borman propose the transfer to the White Tower from the Garden Tower, along with Richard's order for a twenty-four-hour guard to monitor them in the White Tower, I found this theory unconvincing. It seems improbable that they would have been relocated to the White Tower. This hypothesis appears to correlate with the site where their purported skeletons were discovered in 1674. Had they been detained behind the bars and windows of the White Tower, their conditions would likely have been more dire than had they remained in the Lanthorn Tower.

I uphold Ashdown-Hill's account, asserting that the boys were relocated to the Lanthorn Tower from the King's Lodgings under appointed guard.

Regarding the final records available concerning the boys, it is essential to acknowledge the division of opinions, as it remains conceivable that either both of them or one has been moved to the Lanthorn Tower.

The prevailing view among many historians is that both boys were alive at the time of their reported deaths, a perspective documented in numerous sources. However, I contend that natural causes may have led to the death of one or both boys rather than homicide. This argument is supported by the research of John A.H. Wylie, who authored a comprehensive essay addressing the possibility of natural causes behind the Princes' demise. Wylie elucidates how the boys may have succumbed to the sweating sickness, presenting a compelling alternative explanation for their deaths:

Edward V and his younger brother Richard may have died in the Tower of London, in the first half of August. 1483, " the month of peak incidence of the English Sweating Sickness. Some of their attendants may have come from the North, any of whom, including Richard III himself, could have been a carrier. The Princes, moreover, were not held captive in a squalid environment.- They were well fed and housed, relatively luxuriously, in the royal apartments of the Tower of London. Their age, ‘sex and social circumstances were those which characterized many of the victims of the fatal illness. Indeed, if Edward V died in 1483 at the age of thirteen years, he would probably have been well into puberty, given that his dietary and cognate circumstances were‘privileged well above average: The Duke of York, although on the young side to succumb would, in the circumstances of the propinquity of his brother, have been vulnerable to a massive exposure to the virus.

This aligns with an account provided by the Dutch priest Desiderius Erasmus, who noted an outbreak of sweating sickness occurring in the same year as the disappearance of Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury. This event was also documented in the York Civic Records, which reported the resurgence of sweating sickness among Henry Tudor's forces before the Battle of Bosworth in August 1485. If substantiated, this information could offer significant insight into debunking the myths related to these events.

Furthermore, there are two accounts concerning Edward V that lend additional support to this matter. Following the dismissal of the Princes’ attendants, Edward's physician, Dr. John Argentine, was the only individual allowed to visit him, albeit without permission to remain in the Lanthorn Tower. In the referenced documentary, Borman cites an account by Mancini, who describes the interaction between Argentine and Edward V. Mancini characterizes the young king as "like a victim prepared for sacrifice," indicating that he sought absolution for his sins through daily confession and penance.

This account supports Ashdown-Hill's theory concerning the mental health of King Edward, suggesting that he may have suffered from depression. I believe that had he received a medical diagnosis, he would likely have been classified with Psychotic Depression; however, this assertion cannot be made with certainty, as I do not possess the qualifications of a medical expert.

If Richard of Shrewsbury had indeed passed away, it indicates that his death may have occurred before Richard III's coronation, which aligns with certain elements of Walpole's account referenced earlier.

This situation prompts an additional inquiry: had one or both of the boys survived, what potential avenues for escape might they have explored?

![Lanthorn Tower [photograph taken on a parapet walk from the Wakefield Tower]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/696bb1_c85a0376473c402d8135f8cbeb986eaa~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_400,h_600,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/696bb1_c85a0376473c402d8135f8cbeb986eaa~mv2.png)

Investigator Watkins sought clarification by interviewing Warder Matt Pryme, a member of the Yeomen Guard at the Tower of London. The Yeomen Guard possesses a captivating history at the Tower, although their tenure commenced after the boys' disappearance following the Battle of Bosworth. Consequently, it is pertinent to inquire about the identity of the guards during that historical period. According to multiple sources, including the House of Commons website, the guards were affiliated with the Serjeant-at-Arms. While it is challenging to ascertain who led the Serjeant-at-Arms at that time, it is known that he and other personnel were responsible for executing directives from the House of Commons, as well as for making arrests. I encountered one particularly intriguing resource that elucidates the appointment process and the responsibilities of those stationed at the Tower of London:

Reflecting the fact that the Serjeant is a Crown appointment, when the House prorogues or dissolves, the Serjeant returns the Mace to the Jewel Tower at the Tower of London and reverts to being a member of the Royal Household, rather than serving the Commons.

The current discussion centres exclusively on the responsibilities within the House of Commons; however, I find it intriguing to contemplate the possibility that Edward IV, Edward V, or Richard III could have appointed individuals to assume those roles. It is frustrating that the existing research does not examine this topic in greater depth, as I am eager to investigate any potential evidence that might be overlooked.

I have also put forward another candidate who could have been responsible - Sir Robert Brackenbury who was the Constable of the Tower at the time of the disappearance of Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury. However, I will find more research on him in due course.

Nevertheless, I will return to the documentary.

The mention of the Serjeant-at-Arms having the authority to traverse the city—and potentially the country—as a member of the Royal Household raises pertinent questions regarding possible connections. If such a connection did not exist, it is difficult to understand how the Princes could have departed unaccompanied. They would have required substantial guard presence if Richard III had indeed authorized their movement; otherwise, their escape would certainly have garnered scrutiny.

The documentary primarily focuses on the White Tower, neglecting to explore other locations in detail. With walls measuring 15 feet in thickness and significant height, escape for prisoners would have been nearly impossible. Given the stringent security measures, one would expect constant vigilance. Thus, the documentary concludes that the Princes could not have exited the Tower without the explicit sanction of Richard III.

Nevertheless, it remains conceivable that they could have orchestrated an escape. Historical accounts provide examples of individuals who successfully absconded from the Tower unnoticed, such as William Maxwell, the 5th Earl of Nithsdale, who disguised himself to evade execution. This implies that the prospect of escaping the Tower may not have been as prohibitive as traditionally believed.

The documentary references a location known as the Sally Port, which merits particular attention. It is noted as the entrance that Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII's second wife, utilized to enter the Tower on the eve of her coronation in 1533. While this location currently serves as a departure point for tours conducted by the Yeoman Guards, I was unable to locate further research to substantiate this assertion, which is indeed frustrating. Nonetheless, it remains plausible to consider that either Edward or both Edward and Richard could have escaped, provided that Richard III had orchestrated a rescue operation for the boys from the Tower of London.

Once again, there is no substantial evidence indicating that Richard III elucidated the circumstances surrounding the Princes' disappearance. Should I encounter additional evidence on this matter, I will address it in a future communication. However, I am sceptical that anyone would have intended harm toward the boys, including Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII. Nonetheless, they vanished from public view after July 1483, which continues to be a profound mystery.

Second Conclusion: Thoughts of Escape:

In conclusion to this second section, I present two distinct observations. While I maintain the position that only Edward V escaped from the Tower of London, I recognize that I could have engaged more thoroughly with this subject matter, considering it required nearly four days to complete this discussion. There exists a substantial body of research to explore and debate. In my assessment, Ashdown-Hill's theories represent the most persuasive sources concerning the fate of the Princes, which accounts for my frequent references to his work.

I have yet to investigate the confession of Sir James Tyrell, and I shall focus on this aspect in the subsequent section. While my perspective may evolve, I anticipate that this confession could either yield a significant breakthrough or simply reiterate previously established events. Only through further inquiry will the truth come to light.

I will conclude this segment and proceed to draft the final portion of the review, during which we will examine the remains of the skeletons believed to belong to the boys, alongside a discovery that is not particularly new. I apologize in advance if the final part takes longer to publish, as it will necessitate extensive research to ensure completeness. I will share it as promptly as possible.

In the interim, I welcome your thoughts on the findings. Please feel free to share your insights in the comments section below.

Author's Note: All resources I have used are based on the sources from these websites and books. This information could change at any time if new evidence comes to light. Find below all the resources I've used including texts from authors who published works (and video content) from 1924 onwards:

References and Sources:

National Library of Medicine 'Were the English Sweating Sickness and the Picardy Sweat Caused by Hantaviruses?'

Paul Heyman 1,2,*, Leopold Simons 1,2, Christel Cochez 1,2

30.Browne J. A Practical Treatise of the Plague. Nabu Press; London, UK: 1720.

34.Mead R. A Short Discourse Concerning Pestilential Contagion. 3rd ed. Sam Buckley; London, UK: 1720.

73.Maclean C. Results of an Investigation Respecting Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases Including Researches in the Levant. Volume 1 Thomas & George Underwood; London, UK: 1817.

Ashdown-Hill, John, 'The Mythology of the 'Princes in The Tower' [Amberley], 2018 [Edition 2 - 2020], 'Introduction' [P2-3], 'What Was Young Edward Really Like? '[P22 - 24], How Was Young Edward Brought Up?' [P29 - 33], 'Why Were The Princes' Declared Bastards?' [P61 - 65]. 'What Did Lord Hastings Do?' [P70 - 71] 'Would Richard III Have Had the Boys Killed [P80 - 83], 'Did "Edward V" Attend Richard III's Coronation?' [P86]

Ashdown-Hill, John, 'The Death of Edward V — New Evidence from Colchester [ESSEX ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY]

Ford, Judith, 'The legacy of the ‘infamous’ Ralph Shaa' [Richardian Bulletin, Mazagine for the Richard III Society], September 2021

Horter-Moore, Pamela Jean, 'The Hastings Hours: A National Treasure' [Edward V 1483]

Jones, Dan, 'The Hallow Crown: The Wars of The Roses and the Rise and Fall of the Tudors' [Faber & Faber], 2014, 'The Only Imp Now Left' [p286, 292 - 298]

Kendall, Paul Murray, 'Richard the Third' (New York: W. W. Norton, 1956)

Mancini, Dominic, 'The Usurpation of Richard the Third' (Translated by C.A.J. Armstrong) [Sutton Publishing LTD], Originally published in 1483 under 'De Occupatione Regni Anglie per Riccardum Tercium'[Modern Edition published on 31st of May 1984]

Moorhen, Wendy E.A., '"William, Lord Hastings and the Crisis of 1483:’ an Assessment. Part 2 (conclusion)" [Richard III Society, P486, P490]

Orme, Nicholas, 'The Education of Edward V' [Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Volume 57, Issue 136, November 1984] [Second edition published12 October 2007]

Ross, Charles, 'Richard III' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981)

Scofield, Cora, 'The Life and Reign of King Edward the Fourth' [London: Longmans, Green and Co.], 1924

Starkey, David, 'Henry: The Prince Who Would Turn Tyrant' [Harper Perennial], Duke of York [p74 - 77]

Wylie, John A.H., 'The Princes in the Tower, 1483 — ~ Death from natural causes?' (Richard III Society) (PI79 - 180)

Website References:

https://webtest.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/commons-information-office/serjeant-at-arms.pdf

Video References:

Lion Television [2024] 'The Princes In The Tower: A Daming Discovery', 3 December 2024. Available at: https://www.channel5.com/show/princes-in-the-tower-a-damning-discovery

History Calling (YouTube) [2024], 'HISTORIAN REACTS TO NEW PRINCES IN THE TOWER EVIDENCE', 6 December 2024. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fqbfd1YicCw

Comments